A 3-month haiku run

Around this time in 2016, I was struggling to keep up with a daily writing routine as other commitments took charge of my day. So I was thinking of doing something different with words as a part of my free writing schedule. Often, when writing students would ask for advice on how to improve on the craft, I’d assign them the task of writing haiku for a few weeks in order to polish up their skills. A writer needs a creative outlet everyday, and the haiku can be a great starting point.

As a form, the haiku is very unique and mysterious. I believe that the true test of a good writer is to be able to produce the most meaning out of the fewest number of words. Brevity is the key. So naturally, I love the form.

In mid-September 2016, I decided to write haiku again; only this time I’d write one a day for 3 whole months. This resulted in 90 haiku over 90 days. Let’s talk about the journey and writing process.

Hold on! What’s a haiku though?

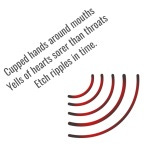

The haiku is a Japanese form of poetry. The traditional Japanese haiku, previously called hokku, is an unrhymed short poem of 17 syllables (on or morae) written in one line. The English haiku is written in 3 lines with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. The traditional haiku is a kind of nature poem or mood poem usually with a seasonal reference (kigo). The haiku is characterised by a “cutting” (kiru) element – a gap or space, whereby 2 juxtaposed ideas or images have a cutting word (kireji) between them which acts as a verbal punctuation to separate the two related ideas. The essence of the haiku lies in illuminating a brief moment in time by connecting two ideas, emotions or images.

Modern English haiku has evolved drastically and can be written on any subject that pleases the poet, instead of limiting the theme to the natural world only. You can break the other rules as well, as long as you’re capturing the core idea of the haiku. Since Japanese does not have separate singular and plural forms for nouns, the haiku is a singular and plural noun in English as well.

The writing process –

A writer lives to observe reality and reimagine it on paper.

My process begins with ideas and observations. As a habit, I fill notebooks, index cards and legal pads with random thoughts I have, well-worded lines that occur to me in a frenzy, objects that I find interesting, unique words and phrases I hear or read, experiences that I wish to write about, dialogue that I hear amongst people around me, doodles and sketches fresh out of my head, and all kinds of strange things that trigger my imagination. I also love lists – a list of unusual similes, a list of obsessions, a list of everything white and round, a list of lists.

All of these things put together work as my sound board when I sit down to write. I play with ideas for the haiku each day and bounce them around till one sticks and I get a good first line out of it. Then the writing follows – framing the lines, finding the right word, drawing parallels, counting the syllables, reading it aloud. This sometimes took under 10 minutes in the morning and at other times, 3-4 hours at 3am after a long day. Once the first draft is ready, the rewriting and brutal editing continues until a fully functional haiku emerges out of the page and hugs me tight.

The journey –

Over the course of three months, my commitment to write everyday was challenged with every ticking moment that passed. If it wasn’t work, it was family. If not family, it was health. If not that, it was just being exhausted after an all-consuming day of events and having to write at hours when I felt the least creative and most unintelligent. And they were plenty more than I’d like to admit.

I also formed an annoying habit. I started counting syllables on my fingers unconsciously with every word that I’d hear – when I was eating, showering, driving, talking. But out of this uncontrollable exercise came the 17 wonderful syllables each day, every day for 3 months. So, my fingers did hurt but it wasn’t entirely futile.

I realised that I could produce so much work consistently, churning out poetry out of tiny nuggets of ideas. I also felt that the heavy uneasiness of posting my work quickly without editing for weeks, began to fade. Writing is very personal and putting your work out there invariably makes you feel vulnerable and anxious. I continued to feel that, but that phase got shorter and shorter with time because doing it became more important than doing it flawlessly.

During this Haiku Hopeful period, I got engaged to my partner of 10 years and amidst all the celebration, I wrote.

When Trump got elected, the struggle was real.

I wrote about change, trust, clutter, the circle of life, the laws of nature, light and darkness, rainy day memories, retrospection and dreams. I wrote about the liberal ideas of free will and certainty, women empowerment and gender roles, childhood and upbringing. I wrote about mundane objects and routine conversations in coffee houses.

So a lot of things, big and small, happened over those 90 days. I changed with them and so did my writing. Some haiku are so bad, I cringe every time I see them. Some are actually good. I take pride in every single one of them. They made me feel like a writer again.